Last year (May 2013), a major update in the area of psychiatric nomenclature was published, namely the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition). This revision occurred after a multiyear interdisciplinary effort by several hundred scientists and clinicians who updated diagnostic criteria and clinical descriptions for all psychiatric disorders.

First, consideration of development across the lifespan led to changes in the overall chapter structure and the order of how individual disorders were listed and described within each chapter. Second, more direct attention was given to assessing gender-specific factors within and across disorders.

Third, while cultural concerns had previously been raised in earlier versions of the DSM, in DSM-5 specific sections on this topic and a cross-cultural assessment procedure were provided. Fourth, the multiaxial system of psychiatric classification was discontinued and all psychiatric and medical disorders were considered on a single axis.

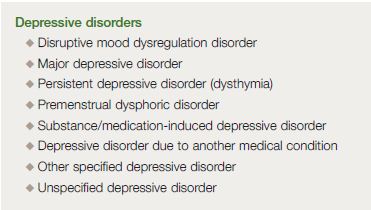

In mood disorders, the most obvious change was the separation of bipolar and related disorders from depressive disorders as individual chapters. There are now 8 specific disorders described in the depressive disorders chapter, including disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, major depressive disorder (including major depressive episode), persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia), premenstrual dysphoric disorder, substance/medication-induced depressive disorder, depressive disorder due to another medical condition, other specified depressive disorder, and unspecified depressive disorder.

Increasing focus has been placed on levels of severity, possible subtypes, and the application of numerous specifiers where appropriate. It is expected that changes in the DSM-5 will enable us to make appropriate changes in diagnostic criteria and specifiers that capture significant advances in clinical research, including advances in neuroscience and genetics.

Depression, a mental health disorder that affects millions worldwide, has seen a significant shift in its understanding and classification with the advent of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). This article explores the intricacies of depression and its redefined categorization under the DSM-5, as proposed by D. J. Kupfer.

Last year (May 2013), a major update in the area of psychiatric nomenclature was published, namely the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition).1,2 This revision occurred after a multi-year effort by several hundred scientists and clinicians who updated diagnostic criteria and clinical descriptions for all psychiatric disorders. Several key points about this update are worthy of comment.

First, this intensive activity, sponsored primarily by the American Psychiatric Association (APA), was conducted in parallel to a similar effort to update the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). Thus, the goal of eventually developing a single classification for mental disorders to be used throughout the world was facilitated by comparable timelines.3

Second, recent advances in clinical and neuroscience research have stimulated numerous discussions—even debates—on how to best integrate such findings into standardized diagnostic criteria.4-6 As a result of 13 international conferences and meetings conducted between 2003 and 2008, a greater focus on four important issues was achieved. First, consideration of development across the lifespan led to changes in the overall chapter structure and the order of how individual disorders were listed and described within each chapter.

Second, more direct attention was given to assessing gender-specific factors within and across disorders. Third, while cultural concerns had previously been raised in earlier versions of the DSM, in DSM-5 specific sections on this topic and a cross-cultural assessment procedure were provided. Fourth, the multiaxial system of psychiatric classification was discontinued and all psychiatric and medical disorders were considered on a single axis.

- Adapted with permission from reference 1: American Psychiatric Association.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th Ed.). Arlington, VA:

- American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. © 2013, American Psychiatric Association.

- All rights reserved.

In the final stages of the review process, the enthusiasm for the inclusion of multiple genetic and neuroscience biomarkers as diagnostic criteria was tempered by the realization that, in most cases, the data were not as definitive as many had hoped.7 However, it is likely that the next edition, even a DSM-5.1, should be forthcoming in much less than the 20-year span between DSM-IV and DSM-5.

By that time, it would be expected that more diagnostic biomarkers could be included. On this path toward increased use of biological markers for specificity of diagnosis, a larger number of subtypes and specifiers for more precise assessment have been included in DSM-5.

All of the above factors directly affected the sections devoted to mood disorders in DSM-5. The most obvious change was the separation of bipolar and related disorders from depressive disorders as individual chapters.

Depressive disorders

Given our primary interest in depressive disorders for this report, it is appropriate to point out first the major changes in the depressive disorders chapter. As indicated in Table I, there are now 8 specific disorders described in this chapter, including disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, major depressive disorder (including major depressive episode), persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia), premenstrual dysphoric disorder, substance/medication-induced depressive disorder, depressive disorder due to another medical condition, other specified depressive disorder, and unspecified depressive disorder.

Consistent with previous DSM versions, attention is given to issues of duration, timing, and presumed underlying causes. As discussed later in this review on changes to depressive disorders, increasing focus has been placed on levels of severity, possible subtypes, and the application of numerous specifiers where appropriate.

A new diagnosis has been added to reflect increasing concern about inappropriate and excessive use of bipolar diagnoses in children. This diagnosis, disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD), should be used to diagnose children under the age of 12 with persistent irritability and severe behavioral dyscontrol.8

The diagnosis is placed in the depressive disorders chapter since the long-term outcome in these children is most likely to be recurrent depression and anxiety disorders, rather than bipolar disorders.9 Major depressive disorder, including major depressive episodes, underwent very few changes from DSM-IV to DSM-5.

Major depressive disorder is characterized by discrete episodes of at least 2 weeks’ duration (although most episodes last considerably longer) with at least one of two symptoms, either depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure, and involving changes in affect, cognition, and neurovegetative functioning. While the diagnosis can be based on a single episode, in general, the disorder is a recurrent one associated with inter-episode remissions in the majority of cases.

Although the classic features of depression have been preserved, an effort was made to refine the distinction between normal bereavement and the symptoms associated with a major depressive episode. Certainly, bereavement can be associated with a high degree of suffering, but it generally does not result in a major depressive episode.

By eliminating the “bereavement exclusion,” the DSM-5 clarifies that bereavement is typically longer than 2 months (an incorrect implication of the bereavement exclusion). The added footnotes in DSM-5 further specify the symptom picture associated with bereavement-related major depressive episodes, in contrast to uncomplicated bereavement.

In previous DSM editions, a distinction was made between dysthymia and chronic major depressive disorder.10 In DSM-5, the diagnosis of persistent depressive disorder captures both the chronic form of major depression and what was formerly dysthymia, a condition that is present for at least 2 years in adults or 1 year in children.

Major depression may precede persistent depressive disorder, and major depressive episodes may occur during persistent depressive disorder. Individuals whose symptoms meet major depressive disorder criteria for 2 years should be given a diagnosis of persistent depressive disorder as well as major depressive disorder.

- Adapted with permission from reference 1: American Psychiatric Association.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th Ed.). Arlington, VA:

- American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. © 2013, American Psychiatric Association.

- All rights reserved.

The premenstrual dysphoric disorder has been moved from an appendix of DSM IV (“Criteria Sets and Axes Provided for Further Study”) to the depressive disorders chapter in DSM-5. This particular disorder has continued to receive much clinical and research attention, as a specific depressive disorder affecting women.11

Finally, as has been noted previously, substances of abuse, certain prescribed medications, and several medical conditions can be associated with depression-like phenomena. The diagnoses of substance/medication-induced depressive disorder and depressive disorder due to another medical condition recognize these issues.12

In addition, the “Not Otherwise Specified” (NOS) category used in DSM-IV has been separated into “other specified” and “unspecified” depressive disorders.

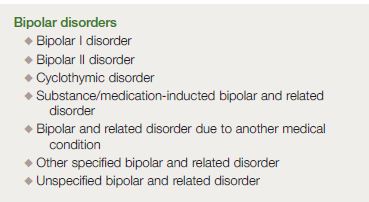

Bipolar disorders

The chapter on bipolar and related disorders is placed between the chapter on schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders and the chapter on depressive disorders. The chapter placement reflects both the extensive clinical data and emerging neuroscience/genetic data providing a bridge across these nosological areas.

The diagnoses included in this particular chapter are bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, cyclothymic disorder, substance/medication-induced bipolar and related disorder, bipolar and related disorder due to another medical condition, other specified bipolar and related disorder, and unspecified bipolar and related disorder (Table II). Bipolar I disorder does not require the presence of psychosis or the presence/history of a major depressive episode.

Nevertheless, most individuals who meet the syndromal definition of mania also experience at least one episode of major depression. The major change to the DSM-5 criteria set for mania is the addition of “increased activity or energy” to criterion A as representing a core symptom of mania and hypomania.

The rationale for this change is to increase the clarity and specificity, as well as improve—in particular—the retrospective diagnosis of mania and hypomania. In contrast, bipolar II disorder includes criteria for both a minimum of one episode of major depression and one episode of hypomania.

As noted above, increased activity and energy have been added to the main criterion of hypomania. Secondly, bipolar II disorder is no longer viewed as a “mild” form of bipolar disorder, but one that is also associated with seriously impaired work and family functioning during recurrent episodes.

As noted below, the diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, mixed episode in DSM-IV, which required the simultaneous presence of syndromal mania and major depression has been replaced with a new specifier, “with mixed features,” that can be applied to either mania or depression but does not require the simultaneous presence of a full episode of both mania and depression. The diagnosis of cyclothymic disorder was not changed from DSM-IV and can be made with adults who are experiencing at least 2 years (for children, a full year) of both hypomanic and depressive periods without ever attaining the full syndromal criteria for an episode of mania, hypomania, or major depression.

As is the case with depressive symptoms, many substances of abuse, certain prescribed medications, and several medical conditions can be associated with manic-like phenomena. These features are recognized in the diagnoses of substance/ medication-induced bipolar and related disorder and bipolar and related disorder due to another medical condition.

Finally, individuals, particularly children and, to a lesser extent, adolescents, who experience bipolar-like phenomena that do not meet the criteria for bipolar I, bipolar II, or cyclothymic disorder can be given the diagnosis of “other specified bipolar and related disorder.” In addition, specific criteria for a disorder involving short-duration hypomania are provided in Section III of DSM-5 with the expectation of encouraging further study of this presentation, which is particularly common in children who present with bipolar-like symptoms.

- Adapted with permission from reference 1: American Psychiatric Association.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th Ed.). Arlington, VA:

- American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. © 2013, American Psychiatric Association.

- All rights reserved.

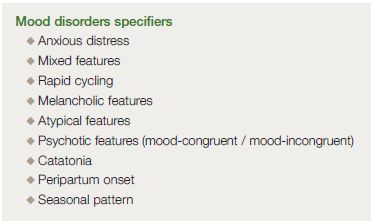

In order to provide a more precise assessment, the DSM-5 work groups sought to identify appropriate specifiers in the mood disorders chapters (Table III, page 523). While there had been traditionally a number of specifiers for mood disorders, DSM-5 also includes a number of new specifiers.

One such change is the mixed features specifier referred to above. It was intended to address difficulties both in the diagnosis of bipolar disorders and depressive disorders. On numerous occasions, patients experience symptoms consistent with both mania and depression, but not enough for them to reach syndromal status.

Therefore, a “with depressive features” specifier was included to be applied to manic or hypomanic episodes when three or more depressive symptoms (depressed mood; diminished interest; psychomotor retardation; fatigue; worthlessness; thoughts of death) are present for the majority of days. In a similar way, the following symptoms may be present during a major depressive episode: elevated mood; increased self-esteem; being more talkative; flight of ideas; increased energy or activity; involvement in pleasurable activities; and decreased need for sleep.

If they are present for the majority of days, then the “with manic/hypomanic features” specifier can be applied. It is felt that this more inclusive approach to mixed features improves the clinician’s ability to note this important phenomenon. The second specifier to be added to the mood disorders chapters is one that notes “with anxious distress.”

It applies to disorders both in the bipolar and depressive chapters. The anxious distress must be present for the majority of days during the episode and includes at least two symptoms (eg, feeling keyed up; restless; difficulty concentrating; fear that something awful might happen; fear of losing control).

Furthermore, with this anxious distress specifier, one can indicate severity by using the number of symptoms present (mild=2; moderate=3; moderate to severe=4-5; and severe=4-5 with motor agitation). Two additional specifiers not restricted to mood disorders can be included for use in mood disorder diagnoses.

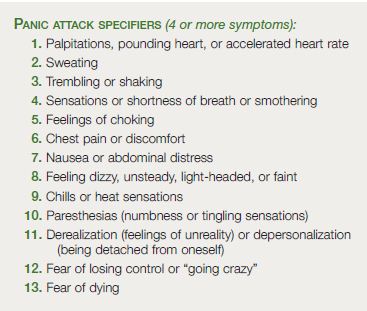

First, a panic attack specifier can be given in the presence of panic attacks during a major depressive episode or even a manic episode. A panic attack is an abrupt surge of intense fear or intense discomfort that reaches a peak within minutes, during which time 4 (or more) symptoms as indicated in Table IV occur.

This surge can occur from a calm or anxious state. Secondly, catatonia has now become a specifier that can be used across different diagnostic disorders.

The catatonia specifier is appropriate when the clinical picture is characterized by marked psychomotor disturbance and includes at least 3 of the 12 features listed in Table V. Finally, with respect to severity specifiers, a change was made when psychosis is present.

While it is known that not all severe mood episodes are psychotic, it is also acknowledged that not all psychotic mood episodes are severe. In DSM-5, there is now an opportunity to indicate psychosis in the absence of high severity.

- Adapted with permission from reference 1: American Psychiatric Association.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th Ed.). Arlington, VA:

- American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. © 2013, American Psychiatric Association.

- All rights reserved.

- Adapted with permission from reference 1: American Psychiatric Association.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th Ed.). Arlington, VA:

- American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. © 2013, American Psychiatric Association.

- All rights reserved.

Other specifiers used in the mood disorder chapters have remained largely unchanged as shown in Table III. Of note, however, the specifier, “with post-partum onset,” has been changed to “with peripartum onset.” This specifier can now be applied to a current major depressive episode or, if full criteria are not met currently, to the most recent major depressive episode if the onset of mood symptoms occurs during pregnancy or in the 4 weeks following delivery.

It is expected that changes to the DSM-5 will be implemented in much less than the 20-year period between DSM-IV and DSM-5. Making appropriate changes to diagnostic criteria and specifiers that capture significant advances in clinical research, including advances in neuroscience and genetics should lead to improved recognition and treatment. It is hoped that such changes will demonstrate the utility of the increased use of specifiers and the identification of diagnostic subgroups that can be validated by objective biomarkers.

The Role of D. J. Kupfer

D. J. Kupfer, a renowned psychiatrist, played a pivotal role in the development of the DSM-5. His contributions have been instrumental in shaping the new classification system for depression, which has been widely accepted and implemented in the mental health community.

Dr David Kupfer has the following disclosures

Consultant to the American Psychiatric Association (as Chair of the DSM-5 Task Force); joint ownership of the copyright for the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI); member of the Valdoxan Advisory Board of Servier International; a stockholder in AliphCom; and he and his spouse, Dr. Ellen Frank are stockholders in Psychiatric Assessments, Inc.

Dr Frank also has the following disclosures: received royalties from the American Psychological Association and Guilford Press; member of the Valdoxan Advisory Board of Servier International; Editorial Consultant for the American Psychiatric Press; and has received honoraria from Lundbeck.

FAQs

How has the classification of depression changed in the DSM-5?

In the DSM-5, the classification of depression has shifted from a categorical approach to a more dimensional one. This means that depression is now recognized as a condition that varies in severity and duration among individuals, rather than being a fixed category.

Why is the DSM-5 important in diagnosing depression?

The DSM-5 is crucial in diagnosing depression because it provides a comprehensive set of criteria that clinicians can use to accurately diagnose and classify the disorder. This helps in formulating effective treatment plans tailored to the individual’s specific needs.

How does the DSM-5 affect the treatment of depression?

The DSM-5 affects the treatment of depression by providing a more precise diagnosis based on the severity and duration of symptoms. This allows clinicians to formulate treatment plans that are more tailored to the individual’s specific needs, potentially leading to more effective outcomes.

What is the significance of recognizing depression as a continuum in the DSM-5?

Recognizing depression as a continuum in the DSM-5 acknowledges the variability in the severity and duration of symptoms among individuals. This is significant because it allows for a more personalized approach to diagnosis and treatment, which can lead to better patient outcomes.

Final Words

The advent of the DSM-5 has revolutionized the understanding and classification of depression. Acknowledging the dimensional nature of depression allows for a more nuanced and personalized approach to diagnosis and treatment.

The contributions of D. J. Kupfer have been instrumental in this shift, paving the way for a more comprehensive understanding of depression and its many facets. As we continue to deepen our understanding of mental health, the DSM-5 serves as a critical tool in guiding our approach to diagnosis and treatment.

For more information about melatonergic antidepressants check our article.

References:

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th Ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

2. Kupfer DJ, Kuhl EA, Regier DA. DSM-5—The future arrived [commentary]. JAMA. 2013;309:1691-1692.

3. Regier DA, Kuhl EA, Kupfer DJ. DSM-5: Classification and criteria changes. World Psychiatry. 2013;12:92-98.

4. Kupfer DJ, First MB, Regier DA. (Eds.) A Research Agenda for DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2002.

5. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Kuhl EA, Kupfer DJ. The conceptual development of DSM-5 [commentary]. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:645-650.

6. Kupfer DJ, Regier DA. Neuroscience, clinical evidence, and the future of psychiatric classification in DSM-5 [commentary]. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:672-674.

7. Kupfer DJ. Neuroscience – Informed nosology in psychiatry: Are we there yet? [invited commentary]. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;7:2-3.

8. Leibenluft E. Severe mood dysregulation, irritability, and the diagnostic boundaries of bipolar disorder in youth. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:129-142.

9. Brotman MA, Schmajuk M, Rich BA, et al. Prevalence, clinical correlates, and longitudinal course of severe mood dysregulation in children. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:991-997.

10. Blanco C, Okuda M, Markowitz JC, et al. The epidemiology of chronic major depressive disorder and dysthymic disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71: 1645-1656.

11. Wittchen HU, Becker E, Lieb R, Krause P. Prevalence, incidence and stability of premenstrual dysphoric disorder in the community. Psychol Med. 2002;32: 119-132.

12. Blanco C, Alegría AA, Liu SM, et al. Differences among major depressive disorder with and without co-occurring substance use disorders and substance-induced depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:865-873.